Love by Whatever Means Necessary: Slightly Stoopid, Pepper & Stick Figure Crowd the Park

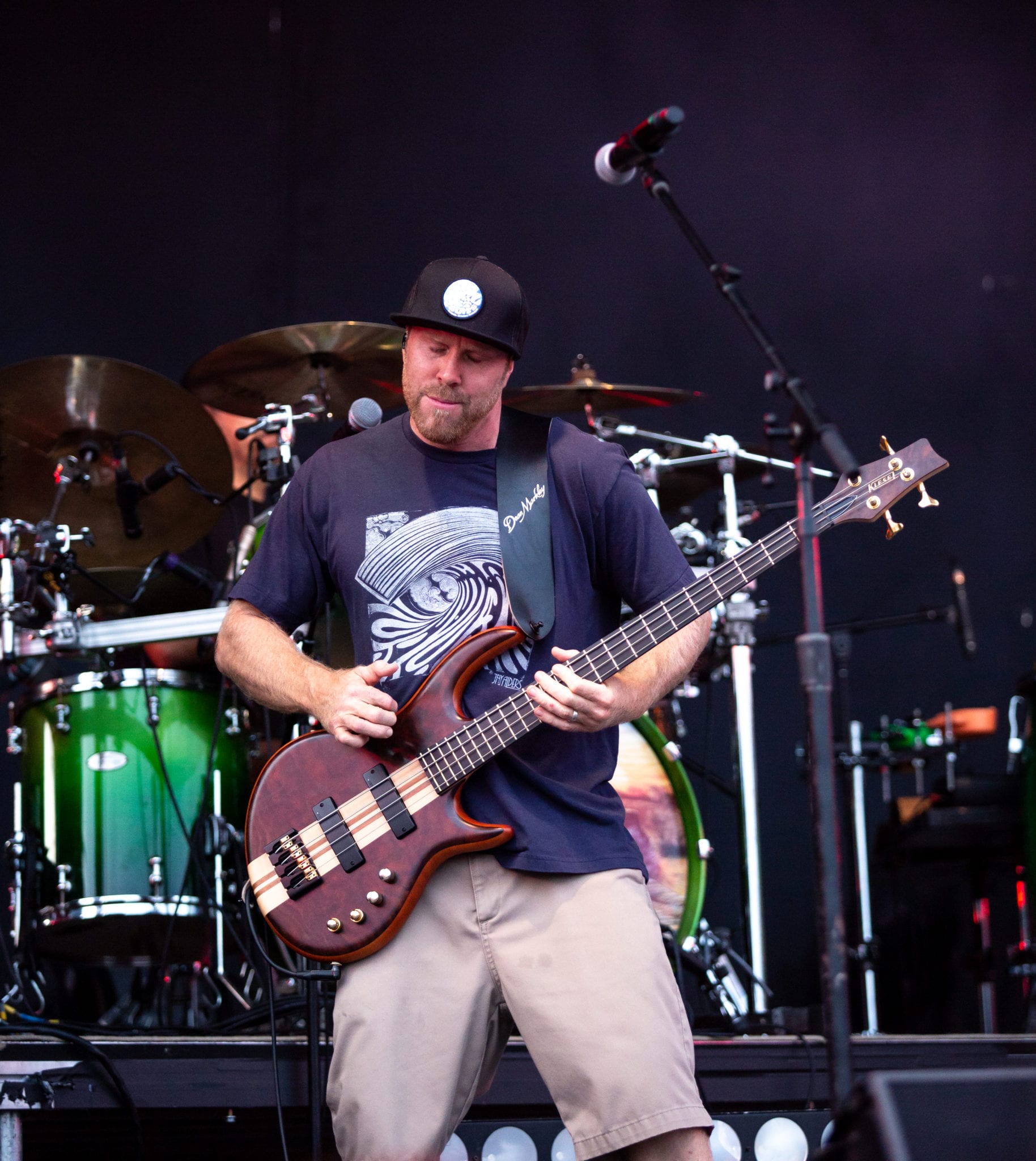

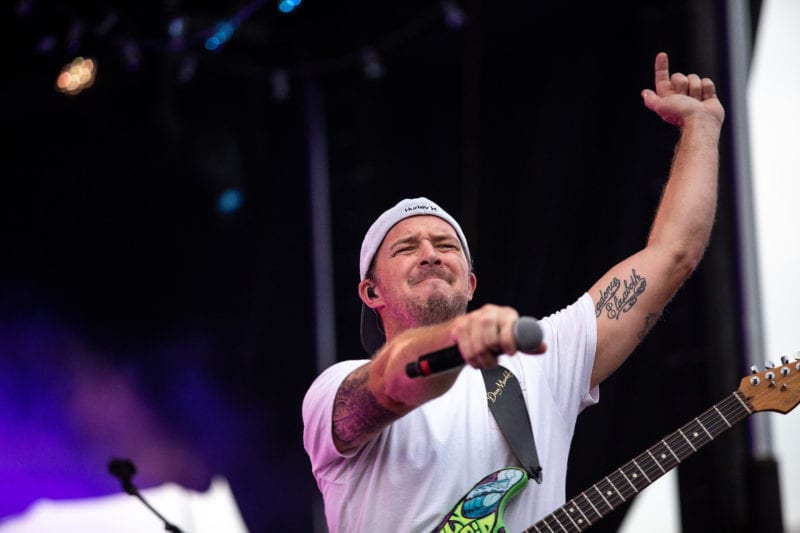

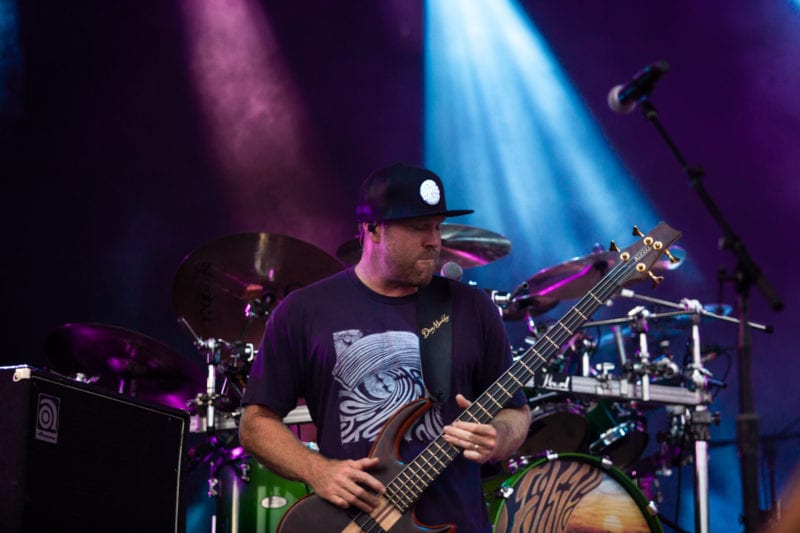

Photos courtesy of Rick Munroe and Mike Lawton

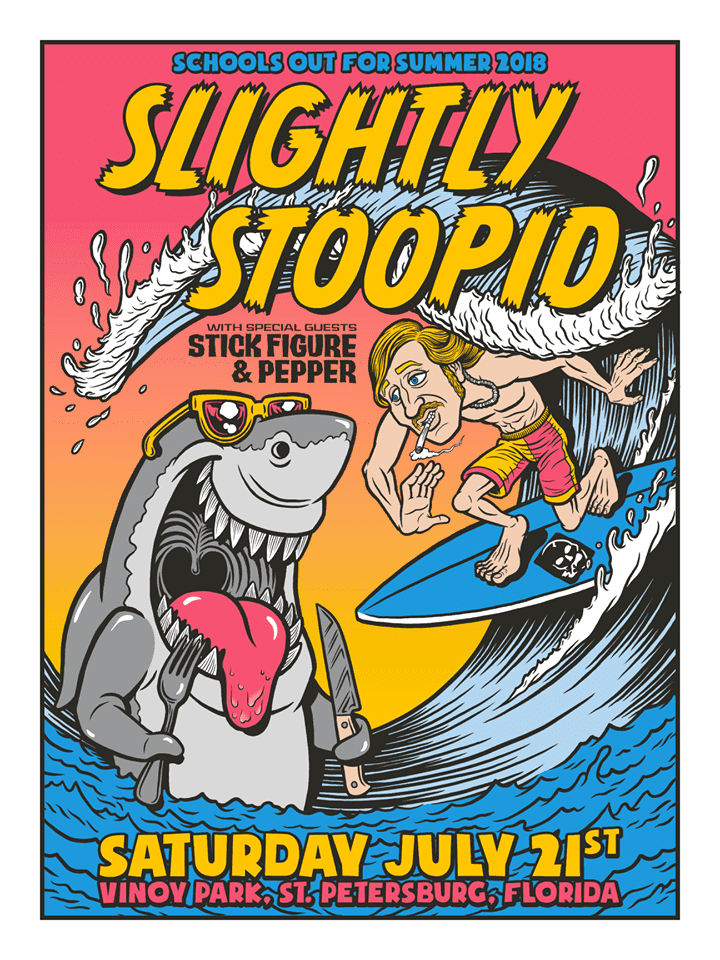

Slightly Stoopid headlined two sold-out show at St. Petersburg’s Vinoy Park (Saturday, July 21) and Sunset Cove Amphitheater in Boca Raton the next day, both supported by Pepper and Stick Figure for their School’s Out for Summer 2018 tour. Since beginning to write for MusicFestNews, I have had the occasion to attend shows of various sizes and degrees, but nothing has yet matched this single lineup event in size. Lines wrapped around will-call and the main gates with fans eagerly waiting hours to see them perform. Pepper was the first to go up at Vinoy Park, and by the time their set was over nearly half the crowd was still attempting to enter the 11-acre venue. (Thus we got no photos of them; we borrowed one from Rick Munroe’s shots in Boca). Spirits remained high despite the drearily sultry summer queue, and, given the mood of the music, most everyone seemed happy to attend.

For those not familiar with the lineup, it is a reggae-inspired dub-ska-rock fusion replete with varying percussion, synthesizers, horns, and trebling riffs. A hybrid of punk, reggae, and hip hop stylings accentuates the vocals which follow the walking bass lines, and the general jam meanderings create a groove-like atmosphere characteristic of the beach lifestyle. In other words, it is music to “vibe” to and draws a massive crowd of various hues. Be it checkered rude boys or henna-adorned starlets, you get a mix of braggadocio and panache alike. As laid back as it may be, the genre itself is anything but blasé and rivals in terms of history some of the most trenchant of its contemporaries.

Renowned rock critic Lester Bangs once said that, in his article “How to Learn to Love Reggae” for Stereo Review in 1977, much of what reggae is about (i.e., millennialism, Haile Selassie, the Golgotha that is Babylon), “[has] nothing to do with you. [It has] nothing to do with me either.” In fact, the Rasta term “Nyabingi” means: “death to white oppressors and their black supporters.” The tension therefore to reggae music lies, on the one hand, with the Rastafari being committed to nonviolence, and, on the other, a militant belief in the retributive power of Jah through whose message words are sacred (thus their idiosyncratic patois).

This is most pronounced in Bob Marley’s political, aesthetic, and moreover ascetic life. Much of what is commonly understood of the reggae tradition has come from that seminal prophet who never tired of singing of love and return and whose ethos continues to permeate the refractions of its subgenres. What is often overlooked is his support of violent opposition on the continent of Africa in the struggles of the peoples of Zimbabwe and South Africa. Cedella Marley, one of Bob’s many children, described his position in an interview with Speech in 1995 as such: “And I think that was the same thing [referring to the message of Malcolm X] Daddy was about, too – unity by any means necessary, even if you have to stick a man in his eye for him to see.

Reggae is street music. Ska and Rock Steady arose from Jamaicans listening to big band and soul music from the U.S. over the radio in the 1950s and ’60s and combining it with the more traditional African Mento beats around the same time as independence and democracy came to the beleaguered nation. Rastafari often came in conflict with the government over their repatriation demands and culture of ganja, which merged with the rude boy culture of diffidence and crime. When the two opposing political factions, the JLP and PNP, came to heads, violence became endemic, with each side inciting divisive gang membership which resulted in a veritable no-man’s-land within the slums of Jamaica. It wasn’t until the late ’70s that the government found in reggae, through its message of unity and history of revolt, a means of bringing the people under a shared identity.

The genre changed forms in many ways and in many places. The characteristic minor key melodies and message of hope and deliverance combined to create a culture inured with oppression a means of expressing a positive message all the while knowing the world not just could or should be — but would be — better. With a large community of Jamaicans emigrating to England, their ex-colonial overseer, the more swinging roots of reggae (i.e., ska) were picked up by mods and skinheads alike — precipitating the 2 Tone Ska movement and its latter U.S. development.

What we’ve come to know of bands like Slightly Stoopid, Pepper, and Stick Figure has much to do with this musical legacy developing into the mixings of dub and a converse turn to the more traditional sounds of the reggae ethos. Like most of the genres and subgenres associated with reggae, dub developed simultaneously with the others in Jamaica and likewise became a force of its own. Due to the fact that sales of reggae music were primarily based on singles, dubbing became a popular practice which often fared better than the original recordings. This practice in turn became a method for live performers to interact with the studio recordings to create and compete with other Dance House-inspired genres in a musical diversity of tactics.

So, why the history lesson? To the untrained eye (or, rather, ear) much of the genre that makes up the scene can seem indistinguishable. It is commonplace within reggae that multi-track albums are only noteworthy as compilations – that it requires a myriad of perspectives to penetrate into the world of otherwise seemingly formulaic arrangements. In order to decipher the constellations of musicians that make up the scene it is a complicated and layered genre that requires an establishing of the palette in order to appreciate the nuances of style that converge and so trace the tan lines around the whole body of the sound.

The message of unity consistent throughout has created a community of Stoopidheads that continues to pack parks and crowd lawns. Slightly Stoopid has a long history in the tradition, and they have continued to evolve their own sound within the wide parameters that have defined the history of the movement and contribute to this culture of militantly peaceful resistance. It is a clarion call that has seen waves of fans from subsequent generations alike come to the fore and find the means of bringing together swaths of differing demographics under an historically rich banner: love by whatever means necessary.